Reporter: Ígor Passarini

Editor: Maurício Angelo

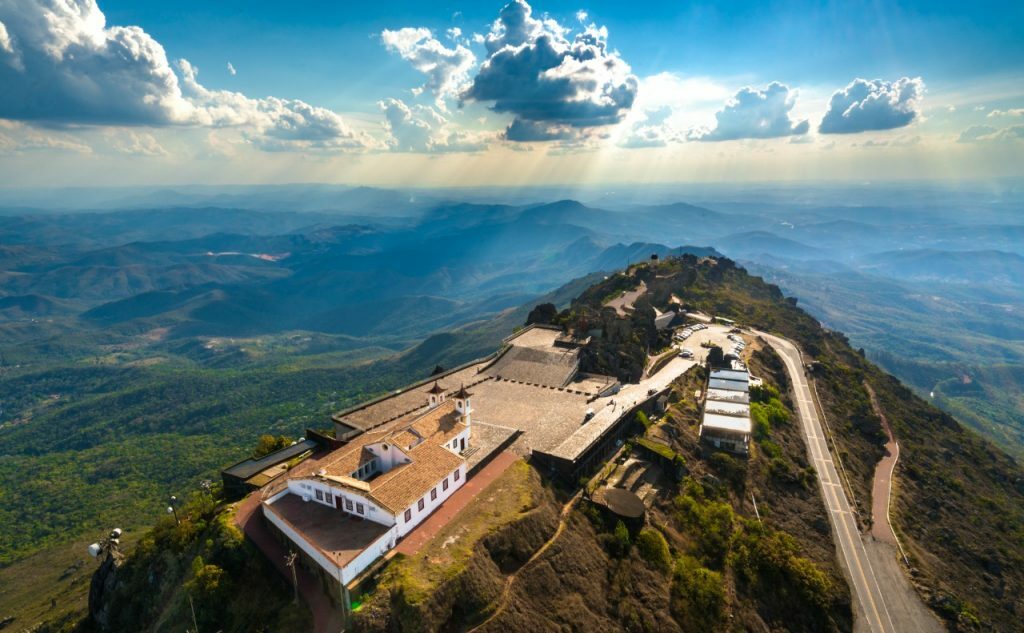

“The governor is calling it the Lithium Valley, when in fact it is the Jequitinhonha Valley. A valley that has its own identity, that has its own people. It is not simply a place for exploration,” warns Cleonice Pankararu, one of the leaders of the Aldeia Cinta Vermelha-Jundiba indigenous land, formed by the Pankararu and Pataxó people, and located on the banks of the Jequitinhonha River, in Araçuaí, Minas Gerais.

The project launched by the governor of Minas Gerais, Romeu Zema (Novo) last year in New York, invited foreign mining companies to explore the mineral in the state. Since then, the government has made promises of development and prosperity, with the creation of jobs, payment of taxes and improvement of the quality of life of the communities.

However, this is not the reality that the population of the Jequitinhonha Valley has faced since the lithium boom begin under the government of Jair Bolsonaro, who opened the national market by decree in July 2022, as shown by the Mining Observatory.

Considered a strategic mineral, lithium has come to occupy a prominent place in Brazil’s race to become one of the global leaders in the energy transition. The growing demand and high profitability of exploration have attracted mining companies and politicians, who are lobbying for more flexible environmental protection, tax payments and compromise the transparency in processes.

Photo: Sigma Mining in Jequitinhonha. Credits: Cleonice Pankararu and Uakyrê Pankararu

The Mining Observatory needs readers to continue working on behalf of society to prevent the ongoing neo-extractivism from jeopardizing a just energy transition. Make a one-time or recurring donation on PayPal.

No health, housing and security

“The population has grown too much, and we have felt the impacts on the economy because the cost of things in commerce has gone up a lot. Hospitals are also overcrowded, due to people who have come to work for the company. And there is the issue of violence, insecurity, especially against women. It has gotten worse”, reveals Pankararu.

According to the leader of Aldeia Cinta Vermelha-Jundiba, it has become impossible to rent properties in the city. “Students from rural areas, like here in my community, sometimes have to pay rent to be able to study and many can’t anymore because the price has gone up. They can’t find any more space”, he said.

José Nelson, an agent for the NGO Cáritas in Araçuaí, confirmed the complaints made by his fellow countrywoman. While talking to the Mining Observatory, in a video call made on his cell phone, he walked the streets of the city to demand transparency in the resources from mining in public accounts, in the middle of a “carnival” hired by the city government for the city’s anniversary party.

“Money is coming in strong in both municipalities, Araçuaí and Itinga. That’s why the expectation of political change is very important. The group that is there today has a very strong corporatism, made up of merchants and businessmen. And they hang around with the CEOs of companies, drinking whiskey at night,” he said.

According to the Cáritas member, the volume of resources is “very violent” and most of the population doesn’t read it this way because they measure the issues “from the bottom up,” being content with the few jobs that are offered to family members, for example, since there is a high demand for manual labor and outsourced services in general.

“Now, what is really good, which is the volume of resources that are flowing through the territory, the city is being left out of this distribution of resources to the community. The hospital hasn’t evolved, health care hasn’t evolved. If we need to be treated in a medical specialty, we have to go to Belo Horizonte or Diamantina,” criticized Nelson. The city councils of Araçuaí and Itinga did not respond to requests for comment made by the Mining Observatory.

Mining sucks water from rivers and raises questions about a just transition

“It is very hard articulate a public policy for collecting rainwater and, on the other hand, companies manage to articulate water permits to extract a large volume from the river. The one-hour permit they have is perhaps enough for the city’s consumption in one or two days. In addition to having an easy permit, they are there contaminating the water, so what kind of energy transition and clean energy is this?”, questioned Rodrigo Pires Vieira, who is one of the coordinators of Cáritas in Minas Gerais.

Last year, a complaint filed by the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB) alleged that Sigma’s activities could directly impact residents’ access to water. “While the rural communities of the Jequitinhonha Valley have access to a 16,000-liter water tank for domestic consumption for 8 months (drought), that is, 2,000 liters per family/month, the concession from the National Water Agency (ANA) for Sigma in the Itinga region is 3.8 million liters/day (100 million liters/month), which would be enough to supply 34,000 families,” the movement stated.

Cleonice Pankararu also warned about the use of river water by mining companies. “The Ribeirão Piauí, which flows into the Jequitinhonha River, is directly impacted because the platform is located right next to it and the Poço Dantas community, which also has indigenous and quilombola communities,” she revealed.

Worsening quality of life, accumulation of waste and lack of prior consultation

The arrival of Sigma in the region, two years ago, coincided with an increase in complaints from residents of the Jequitinhonha Valley about the community’s quality of life.

“It got worse because their way of producing is different. They said they wouldn’t produce waste, but it produces a lot of dust, a lot of explosions,” revealed Pankararu.

According to her, even though the platform is 10km to 15km away, it is an area of mobility for indigenous peoples, who are used to walking a lot. “They arrived without consulting, without trying to find out about the communities. We ourselves were taken by surprise. When we found out, the mining had already been installed,” she added.

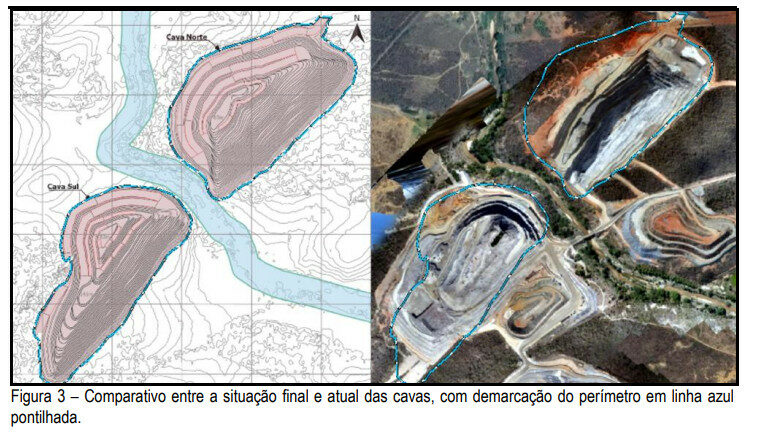

The information that Sigma’s operation does not produce waste is disputed by the licensing process itself at the Environment Secretariat (Semad) and the Superintendence of Priority Projects (Suppri), checked by the Mining Observatory . Sigma’s open-pit mining includes the use of explosives and the installation of five waste piles. An estimated 65% of waste is used for total lithium production, with part of the waste donated to the city government to pave roads with “gravel” – lithium waste. Annual waste production, with the expansion approved this year, will reach 3,380,000 tons of waste per year, according to a report by SEMAD .

Amid the allegations, Sigma calls itself “quintuple-zero” in sustainability

Since its arrival in the Jequitinhonha Valley, the Canadian mining company has sold the project as “green”, “sustainable”, with “zero chemicals”, “zero drinking water”, “zero waste” and “100% prosperity” for the region.

The propaganda was even reinforced with a flashy label during COP 28, in Dubai, last year, when Sigma presented to the world the extraction of lithium in its plant with what it calls “quintuple-zero”. The project’s licensing documents, however, as already demonstrated in this story, contradict the Canadian mining company’s narrative.

In addition to the waste, the concession granted by ANA to Sigma Lithium is valid for 10 years and allows the pumping of water from the Jequitinhonha River 24 hours a day. In total, Sigma can use 3 million and 600 thousand liters of water per day.

IEA–USP Global Cities postdoctoral fellow Elaine Santos, who studies the global lithium market, explained that this attempt to present itself as sustainable is nothing new. “What sets Sigma apart is that it has this robust marketing, so it takes and creates this package of actions within its mining company and sells these practices in a commercialized way,” explained Santos.

The researcher emphasized that each mine has unique characteristics and impacts on specific communities, each with different ecosystems and ways of interacting in the territory. “There is no consensus on these actions or whether this is acceptable or correct. Sigma’s idea of a mining standard also cannot be applied uniformly because mining lithium is not the same as mining iron. So it is not possible to treat this as a model, as they do in a very propagandistic way,” she said.

Elaine also recalled Law Project 2809/2023, which is being processed in the Chamber of Deputies and deals with the “voluntary certification” of green lithium. The agenda has been ready to go to the plenary since December. The project was authored by a number of openly right-wing parliamentarians, many of whom are Bolsonaro supporters, such as Adriana Ventura (Novo-SP), Evair Melo (PP-ES), Coronel Chrisóstomo (PL-RO), Kim Kataguiri (União-SP) and José Medeiros (PL-MT), among others.

“This project shows the strength of this marketing strategy and legitimizes a mining model, which is what Sigma is imposing with these practices,” she highlighted.

Change in the Climate Fund’s budget limit allowed BNDES to grant Sigma Lithium a half-billion loan

In addition to occurring amid new complaints from local communities in the Jequitinhonha Valley, the R$487 million loan (almost US$ 100 million) from the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES) for the expansion of Sigma Lithium, approved in August, was only possible due to significant changes made this year to the National Fund on Climate Change, better known as the Climate Fund.

Each project was entitled to R$80 million and now this amount has increased drastically – to R$500 million every 12 months. To the Mining Observatory, BNDES confirmed that two changes were made in 2024, one in April and the other in September. Only two projects were able to obtain loans above the old ceiling, one for R$90 million and the other for R$98 million, both of which are not mining projects.

“The Climate Fund is open. It is a counter. Companies submit their applications through the customer portal – which is the means to operate a direct line with BNDES”, explained the bank’s Mining and Mineral Processing Manager, Pedro Paulo Dias. According to him, the objective of the program is to encourage companies to move forward with projects that have “this climate ambition”.

A statement sent by the Canadian mining company says that the R$487 million will be used to build the second plant in the Jequitinhonha Valley, between Araçuaí and Itinga, expanding the lithium production capacity from 270 thousand tons per year to 520 thousand tons/year.

The financing will have an amortization rate of 192 months (16 years), with a grace period of 18 months and an interest rate of 7.45% per year. According to Sigma, no asset was required as collateral and the development loan will be secured by a letter of credit issued by a financial institution registered with BNDES.

The requests made to BNDES by the Mining Observatory regarding the contract received the same response. “The financing with Sigma Lithium is still awaiting contracting, so BNDES is prevented from disclosing the requested documents, as they are protected by corporate secrecy – based on article 22 of Law 12,527/2011, combined with article 6, item I, of Decree 7,724/2012”, they wrote.

In addition to the new limit, the program also now allows the possibility of financing up to 100% of projects, in the following six categories: resilient and sustainable urban development; transportation logistics, public transportation and green mobility; energy transition; native forests and hybrid resources; green services and innovations; and green industry. The latter is the category in which Sigma was classified.

The mining companies Sigma and CBL did not respond to questions posed by the Mining Observatory.

Market attracts Australian and American mining companies

The easing measures signed by Bolsonaro and Zema have led to a drastic increase in lithium exploration and mineral research in the Jequitinhonha Valley Region. Until then, only Companhia Brasileira de Lítio (CBL), which is 100% Brazilian, had operated a mine and a chemical plant since 1991.

While some mining companies are in the early stages of their projects, Canadian Sigma Lithium began exploration in April of last year, with the goal of becoming one of the five largest lithium producers in the world. Meanwhile, North American Atlas Lithium and Australian Latin Resources are in the implementation phase.

Latin was purchased by Pilbara Minerals for US$370 million, with the announcement of the acquisition of 100% of the company made during Exposibram 2024, held in Belo Horizonte last month. The project will be carried out in the municipality of Salinas, another of the 14 that make up the now-called “Lithium Valley”, and has a planned investment of US$ 313 million.

“This is a fundamental milestone in our strategy of diversification and global expansion. The Salinas Lithium Project, with its potential to become one of the largest hard rock lithium operations in the world, will be vital to consolidating our leadership position in the battery markets of North America and Europe. We are excited to bring our technical expertise to Brazil and contribute to the sustainable development of the region”, said the mining company’s CEO, Dale Henderson, during a press conference at the event.

The growth of the sector is seen with enthusiasm by Henrique Tavares, manager of the Mining, Metallurgy and Steel area of Invest Minas, a promotion agency created by the state government with the objective of attracting and developing investments.

“Some companies are in the research phase, others in the environmental licensing phase. We expect that at least one more will start operating between 2024 and 2025, and a second one will start operating in the course of 2025. In other words, we will have four companies operating. It is a very promising scenario that will put Minas Gerais at a considerable level of production,” he projected.

The Pure Dynamite report, produced by the Mining Observatory in partnership with Smoke Signal , showed that until Bolsonaro’s decree, lithium exploration and commercialization in Brazil was focused on supplying the domestic market, via CBL, which mainly supplied the medical-hospital sector and the chemical industry.

Fonte

O post “The greenwashing behind Brazil’s lithium boom” foi publicado em 17/10/2024 e pode ser visto originalmente diretamente na fonte Observatório da Mineração